Introduction: Lyme disease was named in 1977 when arthritis was observed in a cluster of children in and around Lyme, Connecticut. Other clinical symptoms and environmental conditions suggested that this was an infectious disease probably transmitted by an arthropod. Further investigation revealed that Lyme disease is caused by the bacterium, Borrelia burgdorferi. These bacteria are transmitted to humans by the bite of infected deer ticks and cause more than 16,000 infections in the United States each year.

|

| From left to right: The deer tick (Ixodes scapularis) adult female, adult male, nymph, and larva on a centimeter scale. |

Vector: Black-legged ticks (Ixodes scapularis) are responsible for transmitting Lyme disease bacteria to humans in the northeastern and north-central United States. On the Pacific Coast, the bacteria are transmitted to humans by the western black-legged tick (Ixodes pacificus). Ixodes ticks are much smaller than common dog and cattle ticks. In their larval and nymphal stages, they are no bigger than a pinhead. Ticks feed by inserting their mouths into the skin of a host and slowly take in blood. Ixodes ticks are most likely to transmit infection after feeding for two or more days.

|

|

National Lyme disease risk map with four categories of risk. (View enlarged image.) |

Risk: In the United States, Lyme disease is mostly localized to states in the northeastern, mid-Atlantic, and upper north-central regions, and to several counties in northwestern California. In 1999, 16,273 cases of Lyme disease were reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Ninety-two percent of these were from the states of Connecticut, Rhode Island, New York, Pennsylvania, Delaware, New Jersey, Maryland, Massachusetts, and Wisconsin.

Individuals who live or work in residential areas surrounded by tick-infested woods or overgrown brush are at risk of getting Lyme disease. Persons who work or play in their yard, participate in recreational activities away from home such as hiking, camping, fishing and hunting, or engage in outdoor occupations, such as landscaping, brush clearing, forestry, and wildlife and parks management in endemic areas may also be at risk of getting Lyme disease.

Prevention and Treatment: It is important to remember that prevention measures can be effective in reducing your exposure to infected ticks, and most patients can be successfully treated with antibiotic therapy when diagnosed in the early stages of Lyme disease. Visit the links below for more information on the following topics:

Prevention and Control

Avoid tick habitats: Whenever possible, avoid entering areas that are likely to be infested with ticks, particularly in spring and summer when nymphal ticks feed. Ticks favor a moist, shaded environment, especially areas with leaf litter and low-lying vegetation in wooded, brushy or overgrown grassy habitat. Both deer and rodent hosts must be abundant to maintain the enzootic cycle of B. burgdorferi. Sources for information on the distribution of ticks in an area include state and local health departments, park personnel, and agricultural extension services.

Use personal

protection measures:

If you are going to be in areas that are tick infested, wear

light-colored clothing so that ticks can be spotted more easily and

removed before becoming attached. Wearing long-sleeved shirts and tucking

pants into socks or boot tops may help keep ticks from reaching your skin.

Ticks are usually located close to the ground, so wearing high rubber

boots may provide additional protection.

The risk of tick attachment can also be reduced by applying insect

repellents containing DEET (n,n-diethyl-m toluamide) to clothes and

exposed skin, and applying permethrin (which kills ticks on contact) to

clothes. DEET can be used safely on children and adults but should be

applied according to Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) guidelines to

reduce the possibility of toxicity.

Perform a tick check and remove attached ticks: The transmission of B. burgdorferi (the bacteria that causes Lyme disease) from an infected tick is unlikely to occur before 36 hours of tick attachment. For this reason, daily checks for ticks and promptly removing any attached tick that you find will help prevent infection. Embedded ticks should be removed using fine-tipped tweezers. DO NOT use petroleum jelly, a hot match, nail polish, or other products. Grasp the tick firmly and as closely to the skin as possible. With a steady motion, pull the tick's body away from the skin. The tick's mouthparts may remain in the skin, but do not be alarmed. The bacteria that cause Lyme disease are contained in the tick's midgut or salivary glands. Cleanse the area with an antiseptic.

Taking preventive antibiotics after a tick bite: The relative cost-effectiveness of post-exposure treatment of tick bites to avoid Lyme disease in endemic areas (areas where the disease is known to occur regularly) is dependent on the probability of B. burgdorferi infection after a tick bite. In most circumstances, treating persons who only have a tick bite is not recommended. Individuals who are bitten by a deer tick should remove the tick promptly, and may wish to consult with their health care provider. Persons should promptly seek medical attention if they develop any signs and symptoms of early Lyme disease, ehrlichiosis, or babesiosis.

Strategies to reduce tick abundance: The number of ticks in endemic residential areas may be reduced by removing leaf litter, brush- and wood-piles around houses and at the edges of yards, and by clearing trees and brush to admit more sunlight and reduce the amount of suitable habitat for deer, rodents, and ticks. Tick populations have also been effectively suppressed through the application of pesticides to residential properties. Community-based interventions to reduce deer populations or to kill ticks on deer and rodents have not been extensively implemented, but may be effective in reducing the community-wide risk of Lyme disease. New approaches such as deer feeding stations equipped with pesticide applicators to kill ticks on deer, and baited devices to kill ticks on rodents, are currently under evaluation.

Early diagnosis and treatment: The early diagnosis and proper antibiotic treatment of Lyme disease are important strategies to avoid the costs and complications of infection and late-stage illness.

Lyme disease vaccine: As of February 25, 2002 the manufacturer announced that the LYMErix� Lyme disease vaccine will no longer be commercially available.

Diagnosis

Clinical

Description:

Lyme disease most often presents with a characteristic "bull's-eye" rash,

erythema migrans, accompanied by nonspecific symptoms such as fever,

malaise, fatigue, headache, muscle aches (myalgia), and joint aches (arthralgia). The incubation period from infection to onset of erythema migrans is

typically 7 to 14 days but may be as short as 3 days and as long as 30

days. Some infected individuals have no recognized illness (asymptomatic

infection determined by serological testing), or manifest only

non-specific symptoms such as fever, headache, fatigue, and myalgia. Lyme

disease spirochetes disseminate from the site of the tick bite by

cutaneous, lymphatic and blood borne routes. The signs of early

disseminated infection usually occur days to weeks after the appearance of

a solitary erythema migrans lesion. In addition to multiple (secondary)

erythema migrans lesions, early disseminated infection may be manifest as

disease of the nervous system, the musculoskeletal system, or the heart.

Early neurologic manifestations include lymphocytic meningitis, cranial

neuropathy (especially facial nerve palsy), and radiculoneuritis.

Musculoskeletal manifestations may include migratory joint and muscle

pains with or without objective signs of joint swelling. Cardiac

manifestations are rare but may include myocarditis and transient

atrioventricular blocks of varying degree. B. burgdorferi infection

in the untreated or inadequately treated patient may progress to late

disseminated disease weeks to months after infection. The most common

objective manifestation of late disseminated Lyme disease is intermittent

swelling and pain of one or a few joints, usually large, weight-bearing

joints such as the knee. Some patients develop chronic axonal

polyneuropathy, or encephalopathy, the latter usually manifested by

cognitive disorders, sleep disturbance, fatigue, and personality changes.

Infrequently, Lyme disease morbidity may be severe, chronic, and

disabling. An ill-defined post-Lyme disease syndrome occurs in some

persons following treatment for Lyme disease. Lyme disease is rarely, if

ever, fatal.

The incubation period from infection to onset of erythema migrans is

typically 7 to 14 days but may be as short as 3 days and as long as 30

days. Some infected individuals have no recognized illness (asymptomatic

infection determined by serological testing), or manifest only

non-specific symptoms such as fever, headache, fatigue, and myalgia. Lyme

disease spirochetes disseminate from the site of the tick bite by

cutaneous, lymphatic and blood borne routes. The signs of early

disseminated infection usually occur days to weeks after the appearance of

a solitary erythema migrans lesion. In addition to multiple (secondary)

erythema migrans lesions, early disseminated infection may be manifest as

disease of the nervous system, the musculoskeletal system, or the heart.

Early neurologic manifestations include lymphocytic meningitis, cranial

neuropathy (especially facial nerve palsy), and radiculoneuritis.

Musculoskeletal manifestations may include migratory joint and muscle

pains with or without objective signs of joint swelling. Cardiac

manifestations are rare but may include myocarditis and transient

atrioventricular blocks of varying degree. B. burgdorferi infection

in the untreated or inadequately treated patient may progress to late

disseminated disease weeks to months after infection. The most common

objective manifestation of late disseminated Lyme disease is intermittent

swelling and pain of one or a few joints, usually large, weight-bearing

joints such as the knee. Some patients develop chronic axonal

polyneuropathy, or encephalopathy, the latter usually manifested by

cognitive disorders, sleep disturbance, fatigue, and personality changes.

Infrequently, Lyme disease morbidity may be severe, chronic, and

disabling. An ill-defined post-Lyme disease syndrome occurs in some

persons following treatment for Lyme disease. Lyme disease is rarely, if

ever, fatal.

|

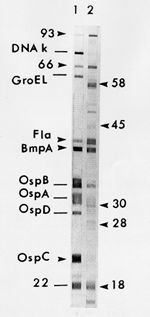

| Image: Western Blot (IgG) Serodiagnostic Testing. |

Diagnosis: The diagnosis of Lyme disease is based primarily on clinical findings, and it is often appropriate to treat patients with early disease solely on the basis of objective signs and a known exposure. Serologic testing may, however, provide valuable supportive diagnostic information in patients with endemic exposure and objective clinical findings that suggest later stage disseminated Lyme disease. When serologic testing is indicated, CDC recommends testing initially with a sensitive first test, either an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or an indirect fluorescent antibody (IFA) test, followed by testing with the more specific Western immunoblot (WB) test to corroborate equivocal or positive results obtained with the first test. Although antibiotic treatment in early localized disease may blunt or abrogate the antibody response, patients with early disseminated or late-stage disease usually have strong serological reactivity and demonstrate expanded WB immunoglobulin G (IgG) banding patterns to diagnostic B. burgdorferi antigens. Antibodies often persist for months or years following successfully treated or untreated infection. Thus, seroreactivity alone cannot be used as a marker of active disease. Neither positive serologic test results nor a history of previous Lyme disease assures that an individual has protective immunity. Repeated infection with B. burgdorferi has been documented. B. burgdorferi can be cultured from 80% or more of biopsy specimens taken from early erythema migrans lesions. However, the diagnostic usefulness of this procedure is limited because of the need for a special bacteriologic medium (modified Barbour-Stoenner-Kelly medium) and protracted observation of cultures. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) has been used to amplify genomic DNA of B. burgdorferi in skin, blood, cerobro-spinal fluid, and synovial fluid, but PCR has not been standardized for routine diagnosis of Lyme disease.

Other Tick-Borne Diseases: Information about other tick transmitted illnesses like Southern tick-associated rash illness (STARI), Babesia infection, and ehrlichiosis can be found at CDC Health Topics A-Z.

More on the History of Lyme Disease: Early in the 20th century, European physicians observed patients with a red, slowly expanding rash (called erythema migrans or EM), associated this rash with the bite of ticks, and postulated that it was caused by a tick-borne bacterium. Then in the 1940s, similar tick-borne illness was described that often began with EM and developed into multi-system illness. Later that decade, spirochete-like structures were observed in skin specimens leading to the use of penicillin for treatment.

Aware of these findings, a physician in Wisconsin diagnosed a patient with EM and successfully treated it with penicillin in 1969. In the mid-1970s, physicians observed clusters of children with arthritis in and around Lyme, Connecticut. Other clinical symptoms and environmental conditions suggested that this was a distinct illness probably transmitted by an arthropod. Researchers linked the presence of EM rash lesions to preceding tick bites and determined that early treatment with penicillin not only shortened the duration of EM but also reduced the risk of subsequent arthritis.

In 1982, spirochetes were identified in the midgut of the adult deer tick, Ixodes dammini (referred herein by its original name, the black-legged tick, Ixodes scapularis) and given the name Borrelia burgdorferi. Finally, conclusive evidence that B. burgdorferi caused Lyme disease came in 1984 when spirochetes were cultured from the blood of patients with EM, from the rash lesion itself, and from the cerebrospinal fluid of a patient with meningoencephalitis and history of prior EM. CDC began surveillance for Lyme disease in 1982 and the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) designated Lyme disease as a nationally notifiable disease in January 1991.

Questions and Answers About Lyme Disease

Q. How do people

get Lyme disease?

A. By the bite of ticks infected with Lyme disease bacteria.

Q. What is the

basic transmission cycle?

A. Immature ticks become infected by feeding on small rodents, such as

the white-footed mouse, and other mammals that are infected with the

bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi. In later stages, these ticks then

transmit the Lyme disease bacterium to humans and other mammals during the

feeding process. Lyme disease bacteria are maintained in the blood systems

and tissues of small rodents.

Q. Could you get

Lyme disease from another person?

A. No, Lyme disease bacteria are NOT transmitted from

person-to-person. For example, you cannot get infected from touching or

kissing a person who has Lyme disease, or from a health care worker who

has treated someone with the disease, or by sexual contact.

Q. What are the

signs and symptoms of Lyme disease?

A. Within days to weeks following a tick bite, 80% of patients will

have a red, slowly expanding "bull's-eye" rash (called erythema migrans),

accompanied by general tiredness, fever, headache, stiff neck, muscle

aches, and joint pain. If untreated, weeks to months later some patients

may develop arthritis, including intermittent episodes of swelling and

pain in the large joints; neurologic abnormalities, such as aseptic

meningitis, facial palsy, motor and sensory nerve inflammation (radiculoneuritis)

and inflammation of the brain (encephalitis); and, rarely, cardiac

problems, such as atrioventricular block, acute inflammation of the

tissues surrounding the heart (myopericarditis) or enlarged heart (cardiomegaly).

Q. What is the

incubation period for Lyme disease?

A. For the red "bull's-eye" rash (erythema migrans), usually 7 to 14

days following tick exposure. Some patients present with later

manifestations without having had early signs of disease.

Q. What is the

mortality rate of Lyme disease?

A. Lyme disease is rarely, if ever, fatal.

Q. Can a person

be reinfected with Lyme disease?

A. Yes. Having had Lyme disease doesn't protect against reinfection.

Some persons have had Lyme disease more than once after re-exposure to

infective tick bites. This stresses the need for continued tick bite

prevention activities such as wearing appropriate clothing when in

tick-infested areas, daily tick checks, and quick removal of attached

ticks.

Q. How many

cases of Lyme disease occur in the U.S.?

A. Lyme disease is the leading cause of vector-borne infectious

illness in the U.S. with about 15,000 cases reported annually, though the

disease is greatly under reported. Based on reported cases, during the

past ten years 90% of cases of Lyme disease occurred in ten states: More

information can be found in the MMWR, March 16, 2001 / 50(10);181-5

| State | Total Number Cases Reported 1989-1998 | Annual Incidence per 100,000 persons |

| New York | 39,370 | 21.6 |

| Connecticut | 17,728 | 54.2 |

| Pennsylvania | 14,870 | 12.3 |

| New Jersey | 13,428 | 16.9 |

| Wisconsin | 4,760 | 9.3 |

| Rhode Island | 3,717 | 37.5 |

| Maryland | 3,410 | 6.8 |

| Massachusetts | 2,712 | 4.5 |

| Minnesota | 1,745 | 3.8 |

| Delaware | 1,003 | 14.0 |

![]() Q. How is

Lyme disease treated?

Q. How is

Lyme disease treated?

A. According to treatment experts, antibiotic treatment for 3-4 weeks

with doxycycline or amoxicillin is generally effective in early disease.

Cefuroxime axetil or erythromycin can be used for persons allergic to

penicillin or who cannot take tetracyclines. Later disease, particularly

with objective neurologic manifestations, may require treatment with

intravenous ceftriaxone or penicillin for 4 weeks or more, depending on

disease severity. In later disease, treatment failures may occur and

retreatment may be necessary. (The Medical Letter, Vol. 42(Issue 1077),

May 1, 2000)

Q. Is the

disease seasonal in its occurrence?

A. Yes, Lyme disease is most common during the late spring and summer

months in the U.S. (May through August) when nymphal ticks are most active

and human populations are frequently outdoors and most exposed.

|

| Map:

Reported cases of Lyme disease in the United States, 1999. |

Q. Where is Lyme

disease most common?

A. Click on the map at right that shows reported cases of Lyme disease

in 1999 by patient's county of residence. Generally, most Lyme disease is

endemic in the northeastern and upper midwest states.